History and Educational

Learn about the history of Halifax and NS. Places listed here are National Historic sites of great interest and importance in understanding Halifax and Nova Scotia’s roots.

The Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 is Canada’s sixth national museum. Their mission is to share the ongoing story of immigration to Canada—past to present and coast to coast to coast. The Museum is located in the Pier 21 national historic site at the Halifax seaport where nearly one million immigrants landed in Canada from 1928 to 1971.

From immigration terminal to national historic site to national museum of immigration, our own story of becoming has its twists and turns.

Countless Journeys. One Canada.

Journeys of courage, hope, hardship and resiliency are at the heart of the immigrant experience. Understanding these journeys helps us understand ourselves and our country.

Their exhibitions are rich with first-person accounts, intimate oral histories, archival photographs, artifacts and immersive experiences. We explore themes of journey, arrival, belonging and contributions situated within larger historical, political and social contexts.

The Museum is the trusted caretaker of the individual voices that, woven together, reveal Canada’s ongoing story of identity and belonging.

120 yerel halk öneriyor

Pier 21'deki Kanada Göç Müzesi

1055 Marginal Rd

The Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 is Canada’s sixth national museum. Their mission is to share the ongoing story of immigration to Canada—past to present and coast to coast to coast. The Museum is located in the Pier 21 national historic site at the Halifax seaport where nearly one million immigrants landed in Canada from 1928 to 1971.

From immigration terminal to national historic site to national museum of immigration, our own story of becoming has its twists and turns.

Countless Journeys. One Canada.

Journeys of courage, hope, hardship and resiliency are at the heart of the immigrant experience. Understanding these journeys helps us understand ourselves and our country.

Their exhibitions are rich with first-person accounts, intimate oral histories, archival photographs, artifacts and immersive experiences. We explore themes of journey, arrival, belonging and contributions situated within larger historical, political and social contexts.

The Museum is the trusted caretaker of the individual voices that, woven together, reveal Canada’s ongoing story of identity and belonging.

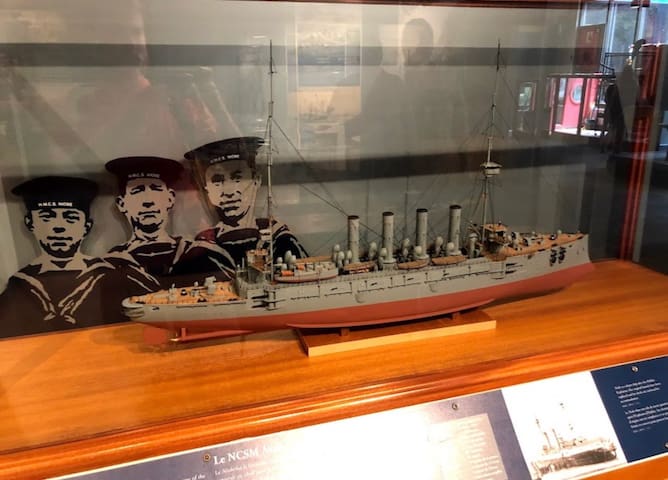

Located in the heart of Halifax’s historic waterfront, there’s no better place to immerse yourself in Nova Scotia’s rich maritime heritage than the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic.

From small craft boatbuilding to World War Convoys, the Days of Sail to the Age of Steam, the Titanic to the Halifax Explosion, you’ll discover the stories, events and people that have come to define this province and its relationship with the sea.

164 yerel halk öneriyor

Atlantik Denizcilik Müzesi

1675 Lower Water StLocated in the heart of Halifax’s historic waterfront, there’s no better place to immerse yourself in Nova Scotia’s rich maritime heritage than the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic.

From small craft boatbuilding to World War Convoys, the Days of Sail to the Age of Steam, the Titanic to the Halifax Explosion, you’ll discover the stories, events and people that have come to define this province and its relationship with the sea.

Halifax Citadel is a large, stone early 19th-century British fortification located atop Citadel Hill, in Halifax, Nova Scotia. The walled citadel is surrounded by an expansive grassed glacis descending to the commons on the west side and downtown Halifax on the east side. It is the most prominent fortification in a network of defensive works that have historically guarded Halifax, its dockyard and its harbour.

HERITAGE VALUE

Halifax Citadel was designated a national historic site because of:

- its role in the development of Halifax as one of the four principal naval stations of the British Empire during the 18th and 19th centuries, and because

- it is an important element in the uniquely complete conspectus of shore defences that developed at Halifax between the 18th century and World War II, to defend British and, after 1906, Canadian interests.

The heritage value of Halifax Citadel National Historic Site lies in its commanding location, in the legibility of its found cultural landscape as a substantial 19th-century fortification, and in the integrity of surviving 18th, 19th, and 20th-century remnants of that landscape. These include all historic resources linked to the landward defence of the town and to the harbour defences along the water that protected the naval station.

Although Halifax Citadel was established as a British post in 1749, the present fort dates from the 1828-1856 period and is its fourth generation of defence works. The Citadel was occupied by British forces until 1906, then by the Canadian military as a detention camp during World War I, and as Halifax headquarters for anti-aircraft defences during World War II. It became a national historic site in 1956 and has since been restored for public visitation.

Sources: HSMBC, Minutes, 1965; Commemorative Integrity Statement.

CHARACTER-DEFINING ELEMENTS

Key features contributing to the heritage value of this site include:

- the evolved cultural landscape comprising its star-shaped footprint, the profile of its built features, its open ground, and remnants of 18th-20th-century military activity including the glacis, the footprint of Fort George, extant historic buildings, structures, site roads, remains and landscape features,

- siting on a drumlin centrally located on the peninsula adjacent to Halifax harbour,

- the open ground that surrounds it (the lack of trees on the glacis),

- the 1930s perimeter roadway connecting the Citadel to the town, and roadways, pathways, channels and tunnels providing internal communications,

- viewplanes to the inner harbour, to landward approaches, to other harbour defences, to the town blocks adjacent to the harbour and those historically linked to the Citadel such as Royal Artillery Park, the Commons, and the Public Garden.

The fort:

- the bastion design with star-shaped footprint and profile,

- functional design, found form, materials and spatial relationships of elements including the parade, south-east and north-east salients, the redan, the south-west and north-west demi-bastions and the west front, fort walls, casemates, counter-mine tunnels and musket gallery, the ditch, ravelins and glacis, south magazine, and north magazine (canteen building).

Defensive works outside the fort:

- the siting, mass, design and spatial relationships of extant military resources on the hill including casemates, north and south magazines, two expense magazines on the ramparts, the Cavelier building,

- the found materials of their construction (primarily stone with supplementary brick as structural support in such areas as casemate arches).

Archaeological remains

- the footprints, materials and spatial relationships of early military facilities including gun emplacements on the ramparts (for smooth bores and RMLs), a barracks foundation, cisterns with a drainage system beneath the parade, a tunnel under the glacis' west side.

318 yerel halk öneriyor

Halifax Citadel

5425 Sackville StHalifax Citadel is a large, stone early 19th-century British fortification located atop Citadel Hill, in Halifax, Nova Scotia. The walled citadel is surrounded by an expansive grassed glacis descending to the commons on the west side and downtown Halifax on the east side. It is the most prominent fortification in a network of defensive works that have historically guarded Halifax, its dockyard and its harbour.

HERITAGE VALUE

Halifax Citadel was designated a national historic site because of:

- its role in the development of Halifax as one of the four principal naval stations of the British Empire during the 18th and 19th centuries, and because

- it is an important element in the uniquely complete conspectus of shore defences that developed at Halifax between the 18th century and World War II, to defend British and, after 1906, Canadian interests.

The heritage value of Halifax Citadel National Historic Site lies in its commanding location, in the legibility of its found cultural landscape as a substantial 19th-century fortification, and in the integrity of surviving 18th, 19th, and 20th-century remnants of that landscape. These include all historic resources linked to the landward defence of the town and to the harbour defences along the water that protected the naval station.

Although Halifax Citadel was established as a British post in 1749, the present fort dates from the 1828-1856 period and is its fourth generation of defence works. The Citadel was occupied by British forces until 1906, then by the Canadian military as a detention camp during World War I, and as Halifax headquarters for anti-aircraft defences during World War II. It became a national historic site in 1956 and has since been restored for public visitation.

Sources: HSMBC, Minutes, 1965; Commemorative Integrity Statement.

CHARACTER-DEFINING ELEMENTS

Key features contributing to the heritage value of this site include:

- the evolved cultural landscape comprising its star-shaped footprint, the profile of its built features, its open ground, and remnants of 18th-20th-century military activity including the glacis, the footprint of Fort George, extant historic buildings, structures, site roads, remains and landscape features,

- siting on a drumlin centrally located on the peninsula adjacent to Halifax harbour,

- the open ground that surrounds it (the lack of trees on the glacis),

- the 1930s perimeter roadway connecting the Citadel to the town, and roadways, pathways, channels and tunnels providing internal communications,

- viewplanes to the inner harbour, to landward approaches, to other harbour defences, to the town blocks adjacent to the harbour and those historically linked to the Citadel such as Royal Artillery Park, the Commons, and the Public Garden.

The fort:

- the bastion design with star-shaped footprint and profile,

- functional design, found form, materials and spatial relationships of elements including the parade, south-east and north-east salients, the redan, the south-west and north-west demi-bastions and the west front, fort walls, casemates, counter-mine tunnels and musket gallery, the ditch, ravelins and glacis, south magazine, and north magazine (canteen building).

Defensive works outside the fort:

- the siting, mass, design and spatial relationships of extant military resources on the hill including casemates, north and south magazines, two expense magazines on the ramparts, the Cavelier building,

- the found materials of their construction (primarily stone with supplementary brick as structural support in such areas as casemate arches).

Archaeological remains

- the footprints, materials and spatial relationships of early military facilities including gun emplacements on the ramparts (for smooth bores and RMLs), a barracks foundation, cisterns with a drainage system beneath the parade, a tunnel under the glacis' west side.

Sightseeing

The Halifax Public Gardens were transformed into the urban oasis of today by the amalgamation of two adjoining gardens, a swampy piece of wasteland and a lovely bequest from an estate. The driving force behind this transition was the passion for horticulture of a number of Haligonian citizens. Many were politicians who had the influence to realize their vision.

The transformation began with the formation of The Nova Scotia Horticultural Society in 1836, under the advocacy of Joseph Howe, a politician and journalist. The NSHS’s aim was to advance the art of horticulture and the science of botany through the cultivation of new varieties of plants and cultural practices.

Mr. Howe sought to have a garden for the society supported by public donations, and grants from legislature. Through his efforts a 5.5 acre piece of the Halifax Commons was provided to the society, free of rent in 1841. The cost of running the ‘People’s Garden’ quickly became overwhelming, and a decade after it’s opening, the NSHS had to find ways to support itself. It sold memberships for entry to its garden and only opened to the ‘People’s’ once a week.

To raise money for its operating costs, it also sold its nursery stock and charged admission

for public band concerts.

Twenty-five years later (1866) another politician, John MacCulloch, created the first city-owned public garden on a 2-acre piece of waste land adjacent to an artificial pond and the NSHS garden. While on a trip to Paris, Mr. MacCulloch fell in love with a public square, which he used as the basis for the design of the Public Garden, which was officially opened in 1867 by Chief Justice Sir William Young.

The new Public Gardens continued to grow when a swampy piece of land to the north west of the artificial pond was filled in, and the City gave a grant of $2000 to pay for landscaping. Mr. McCulloch’s successor William Barron, also successfully set his sights on having the city purchase the People’s Garden owned by the deeply indebted NSHS. He combined it with the adjoining Public Garden.

In 1872 Richard Power was hired as the superintendent of the Halifax Public Gardens and given the task of combining all these pieces into a harmonious whole. He began to implement his axially symmetrical plan in the Gardenesque style, in 1875 by planting 2000 trees from the existing stock of the NSHS nursery. Aleés were planted along the perimeter to delineate the Gardens, and the Grande Alleé was planted along it’s centre to merge the whole. The work continued for 4 years culminating with a more natural shape being carved out for the artificial pond, now known as Griffin’s pond.

Many of the main features we associate with the Halifax Public Gardens were added after the completion of Richard Powers plan.

Starting with the Bandstand in 1887, the next 24 years saw the addition of the Pavilion Entrance (for which the main wrought iron gates were ordered), followed by the Jubilee Fountain, the Soldier’s Memorial Fountain, the Gardener’s Lodge, the iron fencing around the perimeter of the Gardens and finally the concrete bridges.

From that point (1911) to the restoration of the Halifax Public Gardens after Hurricane Juan in September 2003, little had been added. After Huricane Juan, new infrastructure replacement and renovation projects were undertaken. The restoration of Horticultural Hall and a new lighting system throughout the Gardens were completed, but no major features were added.

The destruction by Hurricane Juan was the catalyst that brought about renewed interest, energy and love for this special treasure in the centre of our city. All this focus brought money to the Gardens thanks to a radio fundraiser organized by the newly former Public Gardens foundation which saw $1 million raised in a 48 hour period. A new entrance through Horticultural Hall Plaza was built, dominated by a fountain supported by swans. A new pumping system for Griffin’s pond was installed, some beds where re-shaped, the stream was widened and re-planted.

The results are glorious and the talented gardeners and horticulturists at the Gardens have kept them looking vibrant.

Restoration work always continues, that is the nature of a garden and its holdings.

Many of the features in the Gardens are over a century old and in need of some tender loving care or merciful retirement.

234 yerel halk öneriyor

Halifax Halk Bahçeleri

Summer StreetThe Halifax Public Gardens were transformed into the urban oasis of today by the amalgamation of two adjoining gardens, a swampy piece of wasteland and a lovely bequest from an estate. The driving force behind this transition was the passion for horticulture of a number of Haligonian citizens. Many were politicians who had the influence to realize their vision.

The transformation began with the formation of The Nova Scotia Horticultural Society in 1836, under the advocacy of Joseph Howe, a politician and journalist. The NSHS’s aim was to advance the art of horticulture and the science of botany through the cultivation of new varieties of plants and cultural practices.

Mr. Howe sought to have a garden for the society supported by public donations, and grants from legislature. Through his efforts a 5.5 acre piece of the Halifax Commons was provided to the society, free of rent in 1841. The cost of running the ‘People’s Garden’ quickly became overwhelming, and a decade after it’s opening, the NSHS had to find ways to support itself. It sold memberships for entry to its garden and only opened to the ‘People’s’ once a week.

To raise money for its operating costs, it also sold its nursery stock and charged admission

for public band concerts.

Twenty-five years later (1866) another politician, John MacCulloch, created the first city-owned public garden on a 2-acre piece of waste land adjacent to an artificial pond and the NSHS garden. While on a trip to Paris, Mr. MacCulloch fell in love with a public square, which he used as the basis for the design of the Public Garden, which was officially opened in 1867 by Chief Justice Sir William Young.

The new Public Gardens continued to grow when a swampy piece of land to the north west of the artificial pond was filled in, and the City gave a grant of $2000 to pay for landscaping. Mr. McCulloch’s successor William Barron, also successfully set his sights on having the city purchase the People’s Garden owned by the deeply indebted NSHS. He combined it with the adjoining Public Garden.

In 1872 Richard Power was hired as the superintendent of the Halifax Public Gardens and given the task of combining all these pieces into a harmonious whole. He began to implement his axially symmetrical plan in the Gardenesque style, in 1875 by planting 2000 trees from the existing stock of the NSHS nursery. Aleés were planted along the perimeter to delineate the Gardens, and the Grande Alleé was planted along it’s centre to merge the whole. The work continued for 4 years culminating with a more natural shape being carved out for the artificial pond, now known as Griffin’s pond.

Many of the main features we associate with the Halifax Public Gardens were added after the completion of Richard Powers plan.

Starting with the Bandstand in 1887, the next 24 years saw the addition of the Pavilion Entrance (for which the main wrought iron gates were ordered), followed by the Jubilee Fountain, the Soldier’s Memorial Fountain, the Gardener’s Lodge, the iron fencing around the perimeter of the Gardens and finally the concrete bridges.

From that point (1911) to the restoration of the Halifax Public Gardens after Hurricane Juan in September 2003, little had been added. After Huricane Juan, new infrastructure replacement and renovation projects were undertaken. The restoration of Horticultural Hall and a new lighting system throughout the Gardens were completed, but no major features were added.

The destruction by Hurricane Juan was the catalyst that brought about renewed interest, energy and love for this special treasure in the centre of our city. All this focus brought money to the Gardens thanks to a radio fundraiser organized by the newly former Public Gardens foundation which saw $1 million raised in a 48 hour period. A new entrance through Horticultural Hall Plaza was built, dominated by a fountain supported by swans. A new pumping system for Griffin’s pond was installed, some beds where re-shaped, the stream was widened and re-planted.

The results are glorious and the talented gardeners and horticulturists at the Gardens have kept them looking vibrant.

Restoration work always continues, that is the nature of a garden and its holdings.

Many of the features in the Gardens are over a century old and in need of some tender loving care or merciful retirement.

The Halifax Waterfront is one of the most-visited destinations in all of Nova Scotia. Stroll the nearly 4 kilometre boardwalk which spans from the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 to Casino Nova Scotia. Along the way explore museums, browse boutique shops, dine at waterfront restaurants, take a harbour tour, grab a ferry to Dartmouth, watch boats of all sizes come and go, take in a festival, and end the day on a patio watching the sun set over the harbour.

19 yerel halk öneriyor

Halifax Harbour

The Halifax Waterfront is one of the most-visited destinations in all of Nova Scotia. Stroll the nearly 4 kilometre boardwalk which spans from the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 to Casino Nova Scotia. Along the way explore museums, browse boutique shops, dine at waterfront restaurants, take a harbour tour, grab a ferry to Dartmouth, watch boats of all sizes come and go, take in a festival, and end the day on a patio watching the sun set over the harbour.

Food scene

The Bicycle Thief exudes a relaxed, come-as-you-are feel, in an atmosphere that blends Old School style with New School attitude. Drop by for lunch or supper, or pull up a chair to our wicked wine bar for a fantastic glass from our titanic selection. The Bicycle Thief offers North American food with an Italian soul, and legendary cooking that will steal your heart…

171 yerel halk öneriyor

The Bicycle Thief

1475 Lower Water StThe Bicycle Thief exudes a relaxed, come-as-you-are feel, in an atmosphere that blends Old School style with New School attitude. Drop by for lunch or supper, or pull up a chair to our wicked wine bar for a fantastic glass from our titanic selection. The Bicycle Thief offers North American food with an Italian soul, and legendary cooking that will steal your heart…

Enjoy the vibrant essence of Latin cooking

ON THE HALIFAX WATERFRONT.

Led by celebrated Chef Anthony Walsh, Bar Sofia playfully nods to his family’s Argentinian heritage as well as the next generation of food lovers, artists and adventurers.

Bar Sofia is located in the Queen’s Marque district footsteps from the apartment. When you arrive, enter the district through South Chock. Bar Sofia’s entrance faces the district centre.

10 yerel halk öneriyor

Bar Sofia

1709 Lower Water StreetEnjoy the vibrant essence of Latin cooking

ON THE HALIFAX WATERFRONT.

Led by celebrated Chef Anthony Walsh, Bar Sofia playfully nods to his family’s Argentinian heritage as well as the next generation of food lovers, artists and adventurers.

Bar Sofia is located in the Queen’s Marque district footsteps from the apartment. When you arrive, enter the district through South Chock. Bar Sofia’s entrance faces the district centre.

A CULINARY ODE TO NOVA SCOTIA’S LAND, PEOPLE AND HISTORY.

Owning a strong connection to time and place, Drift pays homage to this region’s land, people and history. Celebrating our natural abundance, Drift’s culinary vision is to showcase the East Coast’s most beloved ingredients stemming from a vibrant community of artisans, producers, farmers and fishers.

Working together, Chefs Anthony Walsh and Jamie MacAulay have crafted menus featuring eclectic interpretations of familiar Maritime fare. Whether you’re sampling an incredible variety of raw bar delicacies or tucking into a piping hot lobster pot pie, Drift’s dishes aim to deliver equal parts comfort and surprise.

Also inspired by the surrounding terroir, Drift’s bar program showcases a mix of classic and signature cocktails that highlight local distillers and ingredients, a selection of interesting craft beers, and a 100+ bottle wine list that includes premium local offerings, traditional styles, as well as several organic and biodynamic blends.

Located on the main level of the newly built Muir Hotel, our salon, bar and promenade offer a simple, modern and stylish setting to dine, drink, linger and relax without interruption. Open for breakfast, lunch and dinner daily, late-night drinks and weekend brunch, we warmly invite you to experience a taste of Drift at your leisure.

6 yerel halk öneriyor

Drift

1709 Lower Water StreetA CULINARY ODE TO NOVA SCOTIA’S LAND, PEOPLE AND HISTORY.

Owning a strong connection to time and place, Drift pays homage to this region’s land, people and history. Celebrating our natural abundance, Drift’s culinary vision is to showcase the East Coast’s most beloved ingredients stemming from a vibrant community of artisans, producers, farmers and fishers.

Working together, Chefs Anthony Walsh and Jamie MacAulay have crafted menus featuring eclectic interpretations of familiar Maritime fare. Whether you’re sampling an incredible variety of raw bar delicacies or tucking into a piping hot lobster pot pie, Drift’s dishes aim to deliver equal parts comfort and surprise.

Also inspired by the surrounding terroir, Drift’s bar program showcases a mix of classic and signature cocktails that highlight local distillers and ingredients, a selection of interesting craft beers, and a 100+ bottle wine list that includes premium local offerings, traditional styles, as well as several organic and biodynamic blends.

Located on the main level of the newly built Muir Hotel, our salon, bar and promenade offer a simple, modern and stylish setting to dine, drink, linger and relax without interruption. Open for breakfast, lunch and dinner daily, late-night drinks and weekend brunch, we warmly invite you to experience a taste of Drift at your leisure.

Nature and Trails

Situated in the south end of the Halifax peninsula, this historic 75-hectare wooded area is a great spot for walking your dog, running, biking, or just sitting on a bench contemplating the ocean. Much of the park is wheelchair-accessible.

Point Pleasant Park is open from

5am - 12 am (midnight.

Point Pleasant Park

5530 Point Pleasant Dr